This article was written by our Kidz to Adultz North exclusive sponsor Schuchmann.

This article is about the requirements and quality parameters of sitting positioning. Our thesis is that there is not “one” physiologically and anatomically correct sitting position for a child with a physical disability. The article invites you to think about the everyday activities that are carried out while sitting and to include these in your decision-making process.

In other words, in our view, sitting should be variable and adaptable to the demands of different situations and activities.

Many people spend most of their lives sitting – in an office chair, in the car, during leisure time. This so-called “sedentary lifestyle” characterises our time. Sitting is far less strenuous than the everyday activities that dominated the work and lives of our ancestors just 80 years ago. Of course, this is pleasant – but lack of movement and inactivity can also have harmful consequences: it results in back problems, obesity, reduced resilience, changes in blood values, and a reduction in fitness levels as shown by health statistics.

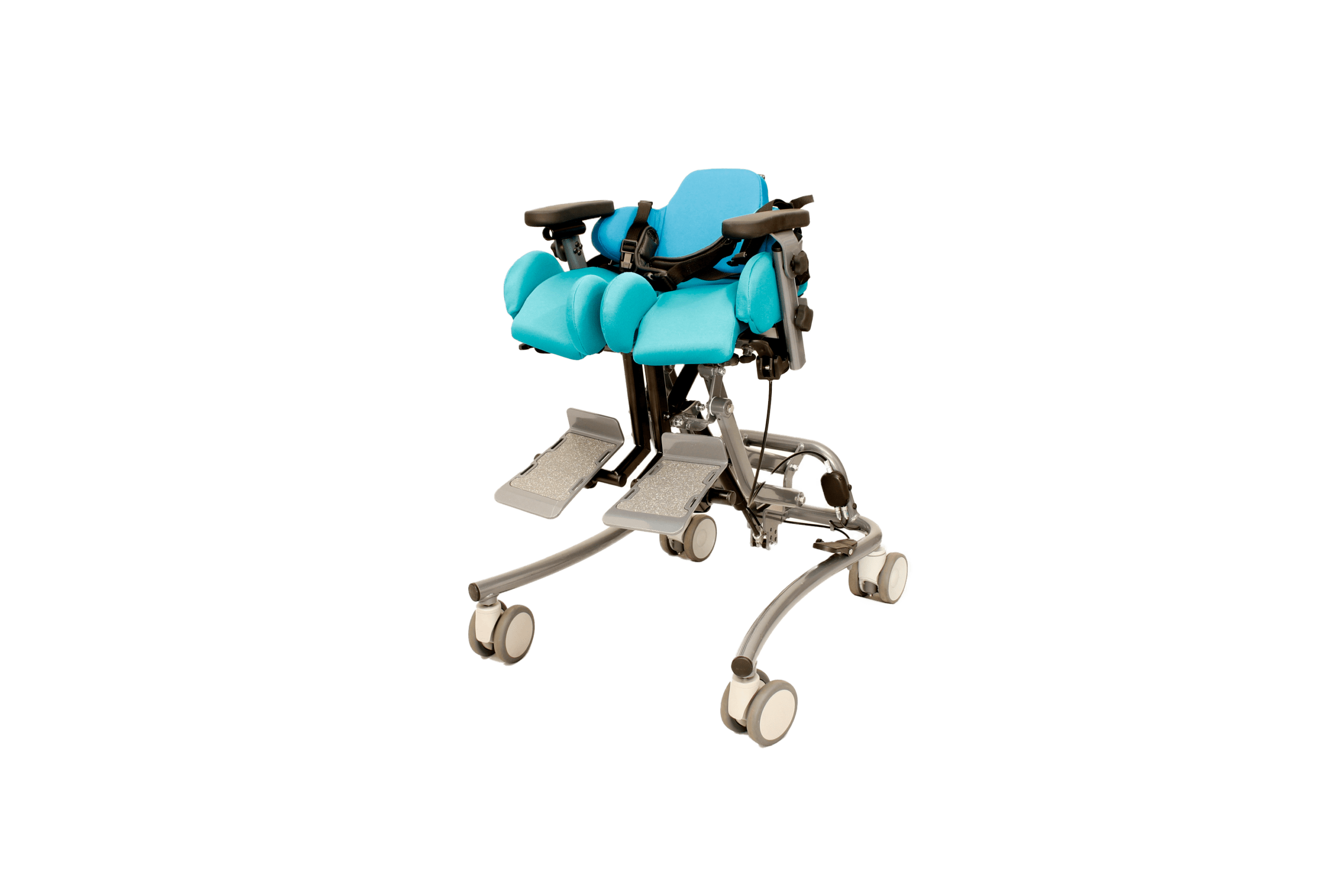

Children whose motor development has stalled are given a therapy chair as their first aid which helps them to sit, hold their heads in order to be in contact with their environment, and to have their hands free for playing. This is correct and important because it increases the ability to be active and participate.

Good therapy chairs save energy when a child sits so that the child has more energy to play and explore.

In our assistive device selection process, we are often focused on, and prioritise, the physical needs of the child or young person. However, seating aids are used throughout the day in different situations and for different needs, and therefore this perspective is not always sufficient. We are called upon to also consider suitability for everyday use and to integrate the therapeutical approach in our clinical reasoning, and to take this into account when deciding on a product or concept.

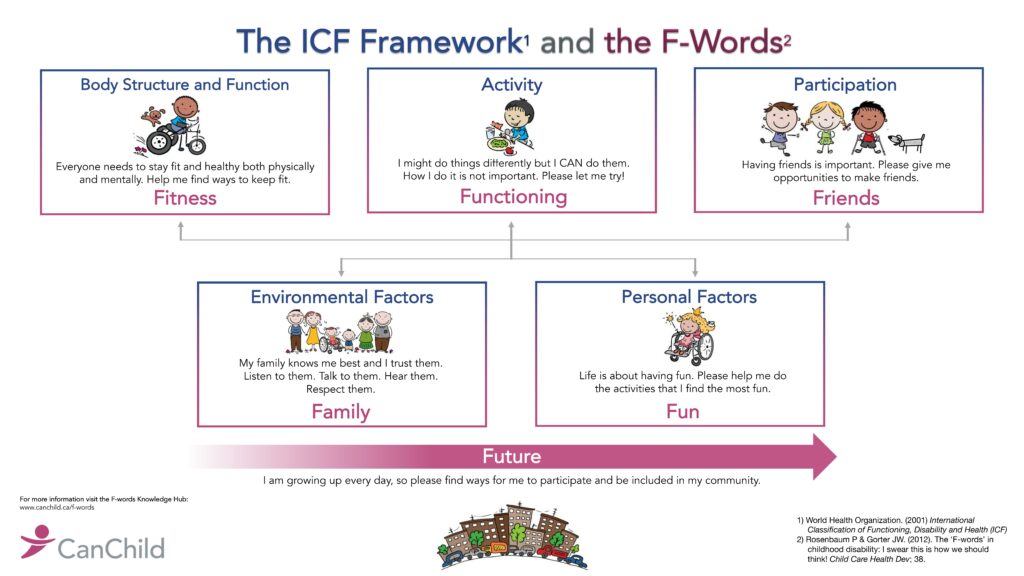

The bio-psycho-social model of the international classification of functioning disability and health (ICF) is a good instrument in this regard, since it is interdisciplinary.

If we regard the components of the ICF presented above as a kind of checklist, we decide which aspect belongs to which component during the selection process. Finally, we can see whether each box has been checked. If this is the case, we will have chosen a therapy chair that fits all the client’s life needs and will therefore be a good all-round aid.

A therapy chair must compensate for weak body functions and structures, promote activities, fit into everyday life, and support participation.

This leads us to the aspects of “variable seating.” What should the therapy chair offer while the child is eating lunch or watching TV?

Naturally, it should make provision for trunk and head control, tone ratios, as well as strength and range of motion (ROM). Common assessments such as the Gross Motor Function Measure (GMFM) and muscle function tests are used to establish an objective perception of physical capabilities.

In many cases, assessments such as the Paediatric Evaluation of Disability Inventory (PEDI), the Children Occupational Performance Measure (COPM) or the Assessment of Motor and Process Skills (AMPS) are also used to analyse activities of daily living. This is done in a clinical situation but should also be done in everyday life – because it naturally makes a difference whether a child is sitting up straight in an examination ward or in a school class. In the clinical situation, many confounding factors that influence the child’s performance in everyday life are eliminated. It is crucial to consider how long, for example, a child remains sitting upright in class in order to provide the appropriate support through the therapy chair. In this regard, communication between colleagues from the different educational and therapeutic contexts, as well as the parents, is important.

With reference to the bio-psycho-social model, we have now briefly looked at the areas of bodily functions, structures, and the activities – and at least touched on participation in educational contexts and family life.

We will now look at aspects related to participation in more detail, because this is where a “thumbs-up or thumbs-down” can make assistive technology provision successful – or condemn it to failure.

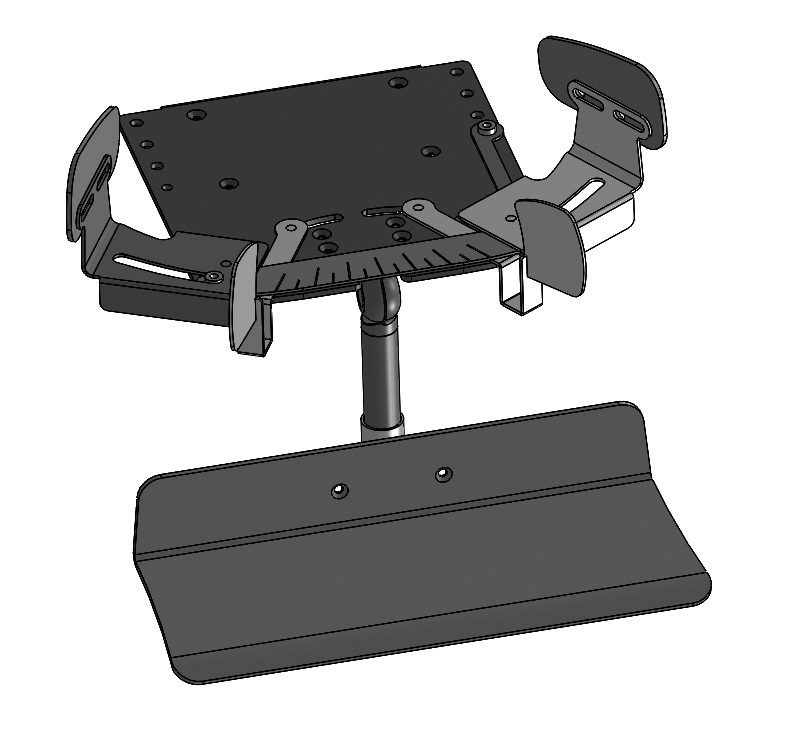

For example, if a therapy chair is selected for school, it is important to check the height of all the tables where the chair will be used. Even if the table in the classroom is easily accessible, it does not mean that the table in the cafeteria or in a special room is easily accessible as well. Does the height adjustment of the base of the therapy chair lead to the correct working height at all tables?

Then there are situations where children play on the floor or wash their hands. Here the chair should also be adjustable and support independence and participation.

The question of how the therapy chair rolls in the school and on the outside grounds also remains to be clarified. Are there perhaps better castors that will make it easier to push the chair? If the chair can be easily pushed and it rolls well, the child will certainly be more inclined to be taken to activities than if the transport is cumbersome and annoying. This is a crucial aspect in promoting participation.

The people around the child are also considered environmental factors in the ICF, and they are probably the most important criterion when it comes to the successful use of the therapy chair.

In this regard, pushing the assistive device is probably one of the easier questions. More important questions might be: How difficult is it for a parent or a caregiver to see that a setting or a positioning aid needs to be corrected?

The best four-point harness has no chance of holding a pelvis where it should be in order to support the straightening of the spine if it is adjusted too loosely. Here we are at a sensitive interface between body structures and the human environmental factor. Experts from many occupational groups who deal with aids in everyday life have only little medical or biomechanical knowledge because this hardly plays a role in their basic training. In their profession, they are confronted with them daily and are expected to deal with them and even make corrections. Therefore, it is of great importance to explain and illustrate how belts are fastened and, above all, what effect they can achieve. This way, the staff on site can see for themselves if something is not right and make the necessary corrections.

An introduction to the biomechanics of sitting can prevent pain and

consequential damage.

We often see that a belt is not fastened properly or is too loose, since people reason that if it is too tight, it is going to hurt. This happens, since they do not take into consideration that if the pelvis is not held upright, the child slides onto the tailbone due to gravity and has no chance to straighten their thorax and control their head. In these cases, taking time to train people and to explain the dynamics is essential so that we can consider together which solution is painless and keeps the pelvic position upright.

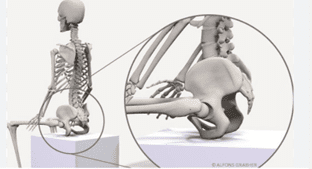

The pelvis as a key point for postural control.

The pelvis is a key point for positioning in sitting. The quality of sitting can be greatly improved if we invest expertise and patience in pelvis positioning.

Starting with the classic 90-degree position in the large joints (hip, knee, ankle), sitting stability can be analysed. There are various assessments for this.

The height requirements for the backrest and the degree of support necessary to create a sitting position that is as active as possible, but not overwhelming, can be derived from this assessment. After all, we would like the child to use their energy to play and explore, and not to maintain the sitting position or to control their heads.

Describing the decision-making process regarding the seating position goes beyond the scope of this post. Attention will therefore now only be given to ways of playing with the hip angle. The forward or backward tilt of the seat has an immense influence on uprightness and seat stability. This in turn is influenced by different tonus ratios on both halves of the body, or by fluctuating tonus due to the underlying neurological disease, or to tonus fluctuations depending on the time of day, or a child’s condition on a specific day.

With time and a trained eye, the parameters of physiological sitting (seat tilt, back height, lateral guidance) should be varied and validated at this point in the selection process to determine the appropriate starting position and situation-specific variations.

The term starting position is chosen deliberately: it must be varied according to the requirements of daily life. This means that the neutral seat surface is tilted forward when the thoracic muscles should be activated. This should certainly not be done during a meal, but why not do it when a child is sitting and playing with other children in a circle? Or why not remove the posterior support for a short time when the fine motor demand is low?

Alternatively, how about giving a lot of support for postural control (e.g. with a waistcoat or chest shoulder strap) when the energy is used for handwriting skills? In other words, why not adjust the position to match degrees of freedom and support to the activities in which the child is engaging?

In this regard, it is often argued that this is too costly and that it cannot be implemented in everyday life. There are two things to say about this:

1. No healthy person can stand to remain in the same position for hours. How do we come to expect this of children and young people with developmental delays?

2. To make varying as easy as possible, the adjustment options must be easy to recognize and easy to use.

The influence on the physical functions of children and adolescents (e.g. improved oxygen supply through active sitting) can hardly be overestimated.

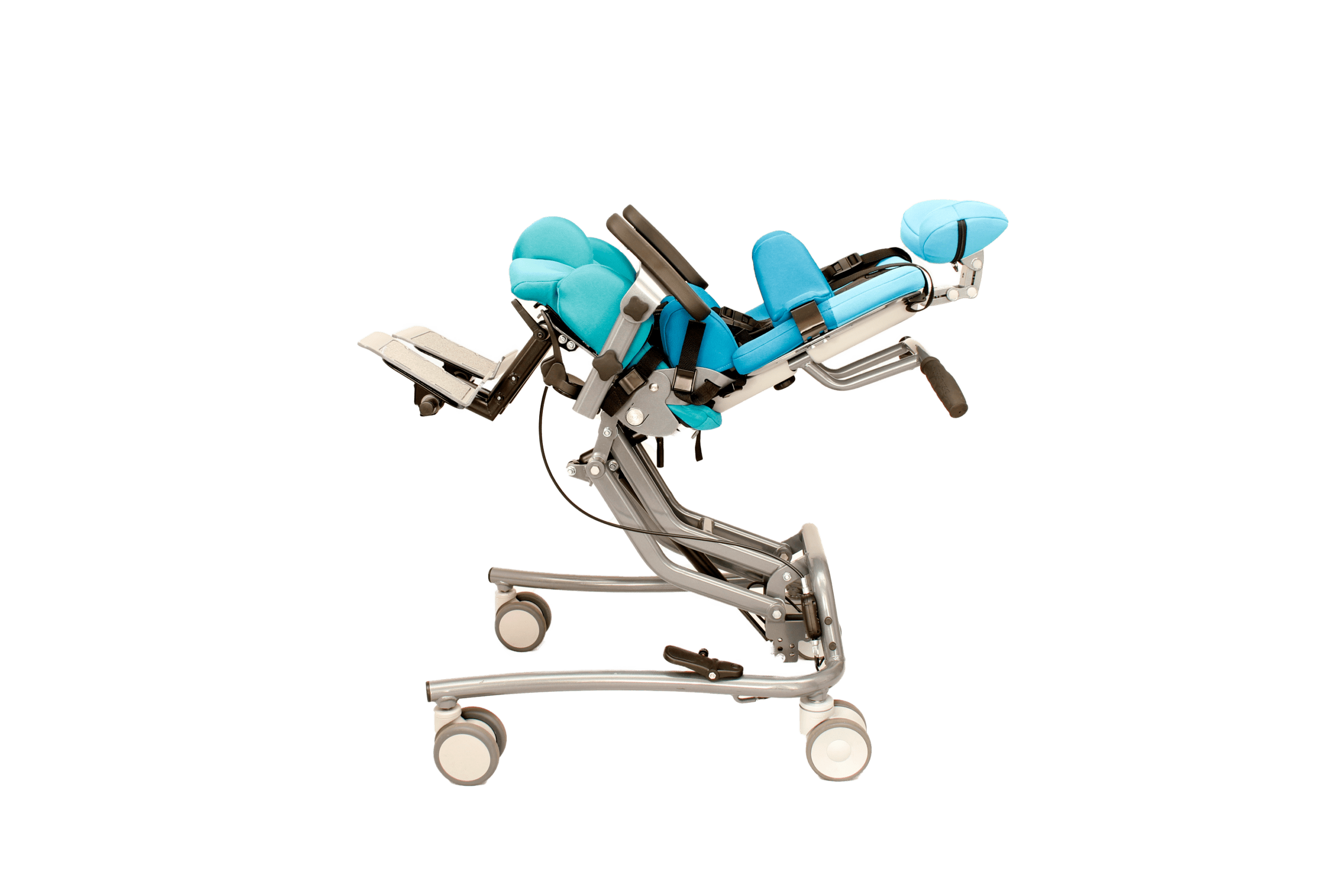

The pictures show the existing support in the form of a wheelchair with a custom-made seat shell. The support provided by the seat shell is correct for many everyday situations. However, at mealtimes (which always require one-to-one support), the position can be changed by Lorenzo using a therapy chair with a removable backrest. This gives the person eating with Lorenzo the opportunity to be behind him and guide his hands while eating.

What difference does it make at mealtime whether the young man is fed, or guides the bread, spoon, or drink to his mouth together with his companion? This situation is more active and self-determined as Lorenzo can influence the pace and choice, so he is more of a partner than a patient. This serves the general paradigm shift in rehabilitation: to bring less care and more accompaniment into the everyday life of people with disabilities.

In this way, therapeutic, medical, and orthopaedic demands find their way into everyday life. They can significantly increase the intensity of rehabilitation and have a greater influence on motor and physical development. It’s all about high repetition rates (repetitive training) and it’s such a shame that we don’t take advantage of these opportunities in everyday life.

Sitting à la française

Another aspect of seat design is considered more in France and Scandinavia. It involves a wide abduction of the hips, which is often combined with a hip angle of over 90 degrees; the concept is often described as “saddle seat”.

This is indeed a good metaphor, because riders often have a very good uprightness and an elegant and weightless appearance. We should let our clients benefit from this, as they are usually struggling against gravity and are pressed down. The wide abduction of the hip leads to a forward tilt of the pelvic blades. This is related to the hip being a ball joint, pulling the femoral heads forward in the abduction of the acetabulum.

This effect can be enhanced if the knees are positioned lower than the hips. This forward tilt of the pelvis supports or provokes the natural lumbar lordosis. In this way, the natural double-S curvature of the spine is triggered where it begins in the anatomy, and provides the impulse for straightening the Thorax.

Hardly anyone can sit upright all day. That is why saddle seats alone are too demanding. Aids are needed that allow a range from a maximum relieving position to a very active sitting position with little support.

People without disabilities unconsciously vary active and passive sitting phases all the time, shifting the body’s centre of gravity and weight. This is an important basic principle that we should follow. Our clients need active sitting positions in their therapy chairs and passive ones throughout the day. In other words, the requirement is that a therapy chair allows these variations and provides comfort in relaxing situations and requires activity when it suits the situation.

A good aid for sitting offers a choice of sitting positions.

The thesis of this article is that we cannot be satisfied with one sitting position for the whole day, but that sitting positions need to adapt to everyday life. This refers to the demands placed on the device: from the seat height adjustment on the base, to the fine adjustment of the hip angle by means of the seat tilt, to the support offered for head control. Finding the right aid requires a precise analysis of the client’s motor abilities, and their fluctuations over the course of the day or through the development of the disease.

We have pointed to the problem that the people who operate the aids in everyday life need to be trained. As a rule, they do not have sufficient anatomical or biomechanical knowledge to be able to assess the sitting positions and correct them if necessary. Yet they are the ones who use them every day. That is why knowledge transfer about the basics of positioning is so important. Even though it is time-consuming and has nothing to do with instruction in the use of the assistive device, information about muscle chains and the influence of joint position are extremely important topics.

If people can assess the change in body dimensions or tone in everyday life, situations where a client sits asymmetrically or with too much weight on the tailbone for weeks can be prevented. Perhaps an Allen key will then no longer be assessed as an adversary but as a help in preventing pain and deformity?

Incorrect applications or supposed reliefs (such as straps that are loosened so they don’t hurt but are then ineffective) can be avoided. Investment in training on the use of aids and their application therefore pays off in the quality of daily use and in terms of avoiding consequential damage such as pain, deformities, and fatigue.

Goal-oriented provision of assistive devices

It is helpful to formulate common and participation-oriented goals when jointly selecting the assistive device and its features in the interdisciplinary team. In many cases, goals such as “the therapy chair enables the use of the hands for fine motor activities” are now being formulated. That is of course correct, and a big step forward compared to goals like “tonus regulation and fine motor improvement”. However, they can become even better.

In times of scarce resources and a restrictive prescription or authorisation policy, the evaluation of the success of an assistive device is of particular relevance. That is why operationalisable goals that can be used to measure the desired success of the provision of aids are so interesting.

At the beginning of this article, we pointed out the importance of an ICF-compliant prescription:

“If we think of the components as a kind of checklist and we can “check” each box at the end of selecting the appropriate assistive device, we are sure to prescribe the appropriate therapy chair because it suits all areas of the client’s life.”

This statement can now be dealt with in more detail in the conclusion. As explained, different aspects need to be taken into consideration when choosing the assistive device. Physical aspects and particularities of the client must of course be considered, and this is covered by the component “body functions and structures”. When choosing a device there is usually sufficient focus on this aspect.

This is similar for activities. Whether it is the use of hands for eating or writing, interaction with others or simply maintaining an upright sitting position, there will always be aspects that decision makers consider here.

As far as participation is concerned, the transition to activities is fluid: meals are taken in groups (family, kindergarten, school), learning takes place in educational institutions, and sitting to communicate with others is a very basic and important argument.

We have also highlighted the importance of environmental factors in this article. Of course, this entails the spatial conditions and the interaction with other furniture or aids. The importance of parents, carers, and educators, who are also considered environmental factors and probably represent a decisive quality feature, should also be considered. Here, investments in knowledge transfer, counselling or coaching are still needed to ensure an optimal use of the assistive device. These factors are listed in the ICF and can be gone through and worked on like a checklist.

Now these pieces of the puzzle just need to be combined into a participation-oriented SMART goal:

Three weeks after delivery of the therapy chair, Lorenzo takes two meals every day in his therapy chair without using the backrest.

The example above explains what is to be achieved by the chair: targeted at an everyday situation, a sitting variation is required, and the goal is measurable, timed and generally understood. It serves the components of the bio-psycho-social model. The selection process has been carried out in a thorough and participation-oriented manner, and is in line with modern rehabilitation and assistive technology.

The requirements and quality parameters for seated positioning are complex. The interdisciplinary care process results in a SMART goal that is ICF-compliant and thus participation oriented.

It is not enough to find the ‘one’ physiologically and anatomically correct sitting position for a child with a physical disability. We are asked to think about the everyday activities that are carried out while sitting and the social aspects, and to include them in our decision-making process.

Sitting should therefore be variable and adapt to the requirements of different situations and activities in everyday life.

This article was written by our Kidz to Adultz North exclusive sponsor Schuchmann.

Comments are closed